Nonprofit Resources

Should Your Church Change its Fiscal Year-End?

If your church uses a calendar year-end of December 31 as its fiscal year-end, you may want to consider whether you would benefit from changing it.

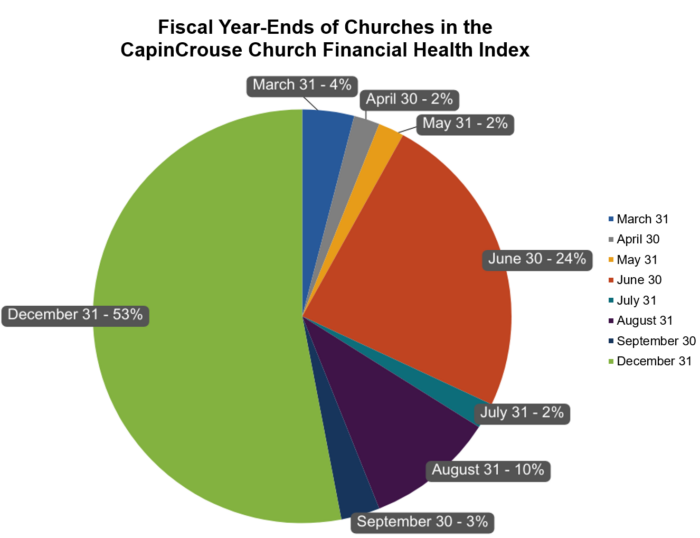

We continue to see more churches moving away from a December 31 fiscal year-end, as illustrated by the data below from churches in the CapinCrouse Church Financial Health Index™ database. A majority (53%) have December 31 year-ends, but this percentage continues to decrease, down 7% over the past six years.

Having your fiscal year end in a month other than December would not result in adverse tax consequences for your church or your donors, and it could provide several advantages. It also could pose several disadvantages, so it’s important to start by considering both.

Potential Advantages

First, a summer fiscal year-end often better reflects a church’s natural business year, since it conforms to the church’s natural annual cycle. It moves the church’s “year-end” to a period when operations and giving are typically at their slowest, which simplifies year-end procedures and facilitates a better measurement of income and financial position. It also gives accounting departments more time to close the books.

Second, the budget process could be completed during the slower months instead of during one of the busiest times of the year for a church — the holidays. One of the biggest advantages of moving away from a December 31 fiscal year-end is that it gives departments adequate time to revise their budget when necessary, especially on expense line items. We see many cases in which churches operate behind budget with the expectation that they will catch up in November and December with a strong year-end appeal to meet the budget with year-end receipts. However, a December 31 fiscal year-end does not allow for adequate revisions on expense lines, as they have already been used regardless of whether the church had strong year-end contributions.

A December 31 fiscal year-end can also make it appear that your church has a stronger cash position than it does, since churches are often “cash-rich” at a December 31 fiscal year-end as donors make contributions ahead of the tax reporting deadline. Finally, a June 30 or other summer fiscal year-end would allow your church to make a May or June appeal that ties into the end of the fiscal year budget, in addition to an annual tax appeal in November and December. However, as the tax code is currently written with the standard deduction, there may be less tax motivation for supporters to make year-end gifts.

Potential Disadvantages

One potential disadvantage is that you may need to determine how to use both your accounting system and donor system to create the calendar-year reports necessary for any tax reporting for your donors. You will need to produce reports on both calendar and fiscal year-ends, increasing the work for your accounting team.

With a non-December fiscal year-end, you will also need to determine whether to keep annual salaries and benefit changes on the calendar year or revise them to reflect the new fiscal year-end. This would include performance evaluations, benefits renewals, and salary adjustments, which could affect both your HR and accounting staff.

Your budgeting and financial reporting will also be impacted. To change your church’s year-end, you will need to do stub period reporting during the transition. A stub period is a reporting period that is either shorter or longer than the typical 12-month reporting period. The stub period starts on the first day of the previous fiscal year-end and ends on the last day of the new fiscal year-end. For example, a church that wants to change its fiscal year-end from January 1 to June 30 could have either a six-month reporting period (January 1 to June 30) or an 18-month reporting period (January 1, 201X to June 30, 201Y).

Stub periods are harder to budget for, and they produce financial information that is not comparable to both the previous and subsequent reporting periods. The 18-month stub period of January 1, 201X to June 30, 201Y in our example would show higher revenues and expenses compared to previous or subsequent fiscal years, primarily because the church is comparing a longer reporting period to a shorter one. Some churches run a 12-month statement for comparative purposes, but that leaves six months of revenues and expenses out — and which six months do you eliminate?

This means that until the church is one year beyond the new fiscal year-end, it won’t have good comparative information. It can take staff time to repeatedly explain this, which can be frustrating. Further, if the church has an audit or review*, additional procedures (and reporting) will be necessary, which will result in additional fees.

Other Considerations

If your church has debt covenants, be sure to talk to your lender about how the fiscal year-end change will impact these measures. Covenants that depend on cash reserves may be easier to achieve at December 31 than at another point during the year.

If your church operates a school, a summer fiscal year-end would help you avoid having different fiscal year-ends for the church and school.

Finally, consider a fiscal year-end that corresponds with the end of a quarter to align with quarterly statements for investments or quarterly reconciliations for items such as Form 941, Employer’s Quarterly Federal Tax Return.

Before you decide to change your fiscal year-end, it’s important to think about the factors above and develop a plan to address them. This would include getting the advice of outside consultants such as accountants and attorneys. And as with any major change, be sure to educate all the stakeholders and address any concerns they may have before moving forward.

With careful planning and implementation, this may be a beneficial decision for your church. Please contact us with any questions or if you would like help evaluating a year-end change for your church.

This article has been updated.

Richard Lindley

Richard is an Audit* Manager at CapinCrouse and has managed audit, review*, and compilation engagements for more than 25 years. He is a former member of the firm’s Church and Denominational Team, and helped draft the CapinCrouse Church Financial Health Index™ and CapinCrouse Church Assessment and related reports. Richard also provides additional services in a variety of areas, including local church consulting reviews, organizational governance, audit committee roles and responsibilities, and internal control. Richard also serves as his church’s finance ministry leader and is a former member of the executive building committee.